This past semester, a service-learning requirement for one of my college classes gave me a glimpse at some of the grim realities that some of our LAUSD students face every day. It also brought back some unpleasant memories. I’m a product of Los Angeles public schools, now majoring in Chicano Studies at California State, Northridge. I’m also an alumna of one of our state’s other large institutions: the prison system.

This is my first semester back in college after an absence of several years. Little did I know that when my father asked me to forge my mother’s signature I was committing a felony that would change the course of my life. But I served my time, and after going through the program at Homeboy Industries, which helps the previously incarcerated readjust to life on the outside, I returned, somewhat shakily, to college.

As part of an initiative to bring ethnic studies into public schools, I would make weekly visits to a high school. As a Latina, a mother, and a student who never saw her own history or culture in a classroom I was all over this. This was also my first real immersion into the world outside of my comfort zones of home, school, and Homeboy.

The morning of my first high school visit, I was feeling jaunty. I even wore a blazer with my Chucks. But when I pulled up to park, my spirits took a nosedive. “This looks just like the jail parking lot,” I thought. One way to enter, one way to exit, with tall, gray metal bars wrapped all the way around. The only thing was missing was an officer in a booth.

I parked my car and looked for an entrance. I saw one–and another uninviting steel fence. You go in a door and check in at the front desk, get a visitor’s pass, and then go through another door that opens up on a courtyard on the other side of the bars.

Now I had to find the right building. There are four different high schools at this facility, with buildings labeled A, B, C, and D–exactly the same as the yards in prison. You can see where I’m going with this, but the echoes of prison didn’t end there.

I made my way into the classroom. Although the teacher had obviously tried to brighten up the place the room was still gloomy. The windows were small with almost no natural light making its way in. The exterior walls had the same tan paint as the prison, and even the light fixtures reminded me of the one I stared at in misery while I was getting a medical exam in prison. I remember it so clearly because I was staring so hard, focusing on it to try to distract myself from that experience.

All this was disturbing to me and started to wonder about the effects this environment might be having on the students.

I gravitated most naturally to the students who weren’t on task, the ones who were acting out or having some other trouble dealing with their day. I sat with them, spent time with them, and helped them with their assignments. One girl told me this was the second time she’d taken this class, and that she couldn’t answer the question because her brain didn’t work. I reassured her that her brain worked just fine. We broke down the question, and I showed her some little tricks that worked for me.

After that I knew that she looked forward to me coming in, even if she rolled her eyes when I would sit next to her. The individual interactions and small one-on-one conversations seemed meaningful to the students, and they meant a lot to me too. But the surroundings were getting to me, as I sat on that chair, at that gray table, almost identical to the table in prison, where I took an assessment exam to determine what job I would get.

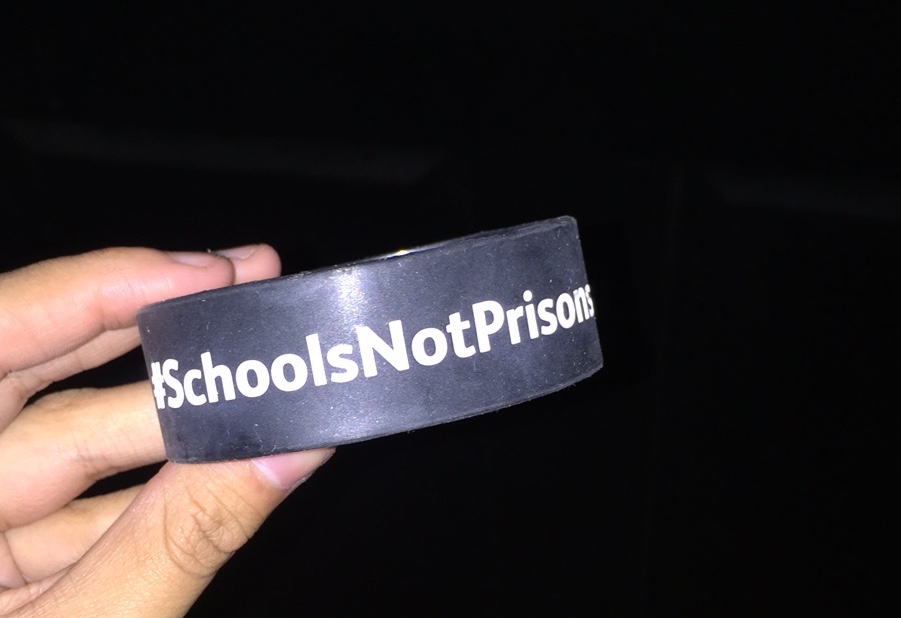

I wanted to run, go get a hot pink spray can and spray it all over the school. Grab a paintbrush and cover the façade and the ugly truth. This school was just like a prison. Some of my classmates also assigned to this school agreed and talked about the school-to-prison pipeline.

This article in Edutopia says that the appearance of schools and classrooms is critical in ensuring that students are learning, and it makes a case for engaging students in the design and upkeep of their own environments. I’m a student too, so I know how my surroundings affect me.

Driving through an affluent neighborhood recently, I noticed another school. There was a fence around the playground, but the front of the building wasn’t separated from the neighborhood by bars. It had a green front lawn, and floor-to-ceiling windows letting in the daylight. I know the high schools like the one where I was working need to be secure for the safety of their students, but do they need to look like prisons?

Steve Barr, the founder of Green Dot Public Schools which manages charter schools and the subject of the short film “The Takeover of Locke High School in Watts,” doesn’t think so. Barr persuaded LAUSD to let him try to turn around one of LA’s worst, which also happened to be my own neighborhood school. According to this article about the film, the school “was gigantic, with 3,000 students. It was dangerous and wild. There were fights, kids smoking pot and playing craps.”

As part of their larger effort, Barr and his team repainted the whole school and fixed up the courtyard. Clearly the transformation involved more than addressing its aesthetics, but, Barr says, “You can’t change a school unless you do that.”

Eventually the way that high school looked got to be too much for me. I’m fortunate to be a part of a program that was understanding of the way the school was triggering flashbacks, and I was able to transfer out of it. I love being at CSUN, looking out of the window of the Chicano House as I type and work. Seeing the nopales outside, with the glow of the bright Los Angeles sun reflecting off the bright orange arts building.

Nuestras Escuelas Parecen Prisiones: Las Escuelas de LAUSD Desencadenó Mi Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático de la Prisión

Este semestre pasado, un servicio de requisito de aprendizaje para una de mis clases de la universidad me dio un entrever a algunas de las tristes realidades que algunos de nuestros estudiantes del LAUSD se enfrentan todos los días. También trajo de vuelta algunos recuerdos desagradables. Soy un producto de las escuelas públicas de Los Ángeles, ahora con una especialidad en Estudios Chicanos en el estado de California, Northridge. También soy una alumna de una de las otras grandes instituciones de nuestro estado en el sistema penitenciario.

Este es mi primer semestre en la universidad después de una ausencia de varios años. Yo no sabía que cuando mi padre me pidió que hiciera falsa la firma de mi madre estaba cometiendo un delito grave que cambiaría el curso de mi vida. Pero me sirvio a mi tiempo, y después de pasar por el programa en Homeboy Industries, que ayuda a la previamente a encarcelados y reajuste a la vida en el exterior, regresé, un poco temblorosa, a la universidad.

Como parte de una iniciativa para traer los estudios étnicos en las escuelas públicas, Me gustaría hacer visitas semanales a una escuela secundaria. Cómo latina, una madre, y un estudiante que nunca vio a su propia historia o cultura en un aula que era todo esto. Este fue también mi primera inmersión real en el mundo fuera de mi zona de confort de un hogar, la escuela y Homeboy.

La mañana de mi primera visita de la escuela secundaria, me sentía alegre. Incluso me puse un suéter con mandriles. Pero cuando llegué al parque, mi espíritu cayó en picada. “Esto se parece al estacionamiento de la cárcel”, pensé. Una forma de entrar, una manera de salir, con barras de metal altas, grises, encerrados por todos lados. Lo único que faltaba era un oficial en una cabina.

Me estacione y busque una entrada,vi una y otro cerca de acero poco atractivo. Usted vaya a esa puerta y registrese en el mostrador de recepción y le van a dar un pase de visitante, y luego vaya a través de otra puerta que se abre a un patio en el otro lado de los barrotes.

Ahora tenía que encontrar el edificio de la derecha. Hay cuatro escuelas secundarias diferentes en esta instalación, con edificios etiquetados A, B, C, y D-exactamente lo mismo que los astilleros de la prisión. Se puede ver a dónde voy con esto, pero los ecos de la prisión no terminaron ahí.

Me dirigí al salón de clases. Aunque el profesor, obviamente, había tratado de iluminar el lugar la habitación seguía siendo sombrío. Las ventanas eran pequeñas, casi sin luz natural haciendo su camino. Las paredes exteriores tenían la misma pintura sombría como en la prisión, e incluso las lámparas me recordaron en la que yo miré en la miseria mientras yo estaba haciendo un examen médico en la cárcel . Lo recuerdo tan claramente porque me estaba mirando con tanta fuerza,concentrandome para tratar de distraerme de esa experiencia.

Todo esto era molesto para mí y comencé a preguntarme acerca de los efectos de este entorno que podría estar teniendo en los estudiantes.

Gravité natural a los estudiantes que no estaban haciendo sus tareas, los que actuaban o que estaba llevando algún otra problema para lidiar con su día. Me senté con ellos, pasé tiempo con ellos, y les ayude con sus tareas. Una chica me dijo que era la segunda vez que había tomado esta clase, y que no podía responder a la pregunta porque su cerebro no funcionaba. Yo le aseguré que su cerebro funcionaba bien. Nos rompió la pregunta, y yo le mostré algunos pequeños trucos que trabajaban para mí.

Después de que yo sabía que ella esperaba que yo me acercaba, incluso ella giró sus ojos cuando me sentaba a su lado. Las interacciones individuales y pequeñas conversaciones uno a uno parecía significativo para los alumnos, y que significaban mucho para mí también. Pero los que estaban alrededor se estaban dirigiendo a mí, me senté en la silla, en esa mesa gris, casi idéntica a la mesa en la cárcel, donde tomé un examen de evaluación para determinar cuál es el trabajo que obtendría.

Quería correr, ir a buscar un spray de color rosa fuerte y poder rociar toda la escuela. Tomar una brocha y cubrir la fachada y la horrible verdad. Esta escuela era como una prisión. Algunos de mis compañeros de clase también asignados a esta escuela estuvieron de acuerdo y hablaron de la tubería de la escuela igual a la cárcel.

Este artículo en Edutopia dice que la apariencia de las escuelas y las aulas es crítico para asegurar que los estudiantes están aprendiendo, y se hace para involucrar a los estudiantes en el diseño y mantenimiento de sus propios entornos. Soy estudiante también, así que sé cómo mi entorno me afectan.

Conducía a través de un barrio de ricos hace poco, me di cuenta de otra escuela. Había una cerca alrededor de la zona de juegos, pero el frente del edificio no se separó del barrio de bares. Tenía un jardín delantero verde, y de piso a techo ventanas dejando entrar la luz del día. Sé que las escuelas secundarias como en la que yo trabajaba necesitan estar seguras para la seguridad de sus estudiantes, pero no necesitan parecerse a las cárceles.

Steve Barr, fundador de Escuelas Públicas Green Dot que administra las escuelas charter y el tema de el cortometraje “La Adquisición de la Escuela Secundaria Locke en Watts,” no lo cree así. Barr persuadió LAUSD para dejarle tratar de dar la vuelta a uno de LA de lo peor, que también pasó a ser mi propia escuela de barrio. De acuerdo a este artículo acerca de la película,la escuela “era gigantesca, con 3.000 estudiantes. Era peligroso y salvaje. Hubo peleas, niños fumando marihuana y jugando dados.Parte de “Cómo su esfuerzo más grande,

Barr y su equipo volvieron a pintar toda la escuela y se fijaron hasta en el patio. Es evidente que la transformación involucró a más de hacer frente a su estética, pero, Barr dice, “No se puede cambiar una escuela a menos que lo hagas con el tiempo.

Eso.”la forma en que la escuela secundaria parecía llegó a ser demasiado para mí. Tengo la suerte de ser parte de un programa que era comprender la forma en que la escuela estaba provocando retrocesos, y tuve la oportunidad de transferir fuera de él. Me encanta estar en CSUN, mirando por la ventana de la Casa Chicano mientras escribo y trabajo. Al ver los nopales al exterior, con el resplandor del sol brillante de Los Ángeles que se refleja en el edificio de artes anaranjado brillante.

Lily Gonzalez

She is a recent cancer survivor and through some years of adversity has risen above all her recent challenges. Lily is a Homeboy Industries graduate and full-time student at California State University, Northridge. She has continued to live her life in South Los Angeles with her two children. She works to show her children that anything can be done with hard work, determination and perseverance even in the face of unimaginable challenges. Her daughter is in a Charter School and she is working to find the right Preschool program for her youngest child.

Latest posts by Lily Gonzalez (see all)

- Denos Una Segunda Oportunidad:Prohíba la Caja en Las Aplicaciones de Colegio - August 21, 2017

- Give Us a Second Chance: Ban the Box on College Applications - August 17, 2017

- De La Prisión a Graduación: Me Lo Gane, Pero Podría Adueñarme del Título? - June 15, 2017

- From Prison to Graduation: I Earned it, But Could I Own it? - June 15, 2017

- A Program like POPS Needs to be Expanded to Meet the Needs of Students with Incarcerated Parents. - July 25, 2016

Kate Crowley

Lily, thank you for this blog. I follow you (not a stalker) and really appreciate your insights. You came to my class at USC and blew us all away. Thank you for increasing all of our awareness. I follow another blog, Timbernook, that advocates returning children to nature, providing movement and play and natural surroundings to them as they learn gleefully.

How different the approach of Timbernook is to the school that triggered you in the LAUSD school system. I am sorry for that experience but so happy that you can articulate your informed opinions on this blog.

keep it up!

Lily Gonzalez

I do not think you’re a stalker at all!! Thank you for the experience at USC and for following the blog.

andrea frazer

I am a sub at LAUSD and I’m honestly getting traumatized. I feel guilt for not wanting to do it anymore (these poor kids need me #Godcomplex) but also I think that they can’t learn as well based on the prison like atmosphere. I found this article because I Googled “LAUSD looks like prison” and found you. I hope you are well. God bless.