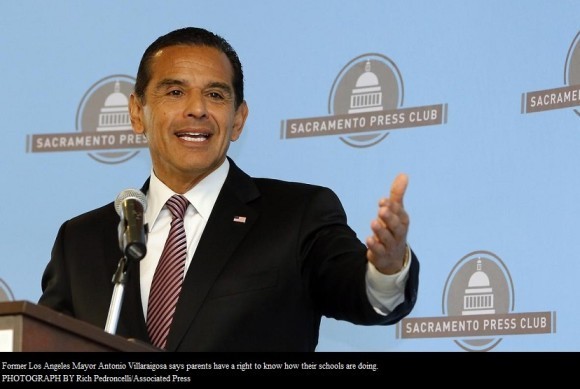

Former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa says parents have a right to know how their schools are doing.

As he eyes a run for governor, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa is spotlighting the lagging academic performance of Latino and African-American students and saying the state should do more to hold schools accountable.

The 63-year-old Democrat says parents have a right to know how their schools are doing and he doesn’t see a contradiction between supporting teachers and holding schools to higher standards.

Villaraigosa, who got into politics as a union organizer for teachers in Los Angeles, did not want to criticize the governor, but his comments differed sharply from Gov. Jerry Brown’s view that the academic performance gap between African Americans and Latinos to other student groups is likely to persist despite government interventions. Brown told CALmatters recently that he doesn’t want his key education policy, the Local Control Funding Formula, to be judged on whether it closes that gap.

“I hear all the time, ‘Well, that’s just the way it is and that’s the way it’s always been,’ ” said Villaraigosa, who was kicked out of a Catholic high school and credits public schools for a second chance. “But that’s just not true. When you hear people make excuses and say, ‘Oh these kids are poor, their parents are English-language learners, they’re foster kids, their parents haven’t gone to college,’ you’re kind of describing the whole lot of us. I can read and write.”

Villaraigosa spoke with CALmatters for an upcoming story about the State Board of Education’s plan to develop a new system for evaluating schools this year. The board is designing a multiple-measures system to replace the state’s test-based measure, the three-digit Academic Performance Index (API), which was suspended in 2014.

The comments from Brown and Villaraigosa frame one of the most contentious elements of the new evaluation plan — how much should the state track and enforce academic standards. Teachers unions say the API was misused and fostered a climate of “test and punish” in schools. Eric Heins, president of the California Teachers Association, said the union doesn’t want to compare and rank schools but rather allow districts and schools to track progress where they see a need for improvement. Some children’s advocates and civil justice groups say that could make it hard for the state to identify and assist underperforming schools.

Villaraigosa, a former speaker of the state Assembly, says schools should be ranked so parents can make informed choices. He penned an opinion piece with The Education Trust-West urging the state to replace the API with “an equal, simple measurement that gives the public a clear-cut way to evaluate school performance.” The questions below have been modified for context and Villaraigosa’s response trimmed for length.

Q: How is California doing when it comes to K-12 schools?

A: I think we’ve got to start with the positives. The good news is California has adopted Common Core and high standards. We’ve embraced innovation, I think there are some 1,200 charter schools. But I think we have to acknowledge that there’s not been enough of a focus on accountability and transparency. And that’s particularly true for low-income students of color who make up a significant majority of K-12 students in California today.

One of my concerns is, and I said this when they … got rid of the API, they said it was going to be a year. It’s already three and we still don’t have a replacement.

Q: Would you say it worked in the board’s favor to wait because the federal Every Student Succeeds Act was passed at the end of last year?

A: That’s not why they waited this long, that’s for sure. When you don’t have measurements you don’t know what’s working and what’s not. We know that for too many poor kids of color, you know, one in five (African-American) kids drop out.

When I became mayor of Los Angeles, we had a 44 percent graduation rate. By the time I left, it was 72. My schools — the 17 schools with 16,000 kids that I took over — had a 36 percent graduation rate and now have a 77.

We focused on accountability. We know that only 10 percent of low-income kids finish college, and most of them don’t go. And that’s just not acceptable. So I believe that the achievement gap is something that we all have to address.

Now look, there’s been some gains among Latino students over the years but California still ranks near the bottom. In eighth grade math, only 15 percent of Latino kids are at grade level compared to 53 percent of white students. In fourth grade reading, Hispanics at grade are 31 percent, for black students it’s 33 points, lower than whites.

I hear all the time, “Well, that’s just the way it is and that’s the way it’s always been.” But that’s just not true. When you hear people make excuses and say, “Oh these kids are poor, their parents are English-language learners, they’re foster kids, their parents haven’t gone to college,” you’re kind of describing the whole lot of us. I can read and write.

Now, is it tougher to teach those kids? Of course it is. That’s why we all have to work together. But the notion that California doesn’t face a crisis; this issue is the economic issue of our time when you look at the new economy. It’s the democracy issue of our time. When you look at who’s not voting, disproportionately it’s poor people, young people. It’s the civil rights issue of our time.

Q: But you saw how difficult it was in Los Angeles.

A: No one is saying it’s easy but you know, there are a lot of things that are hard. It’s connected to the issue of income inequality. If you can’t read and write, you’re not going to be able to successfully go through society, you’re destined to make minimum wage.

I’m not suggesting to you that it’s easy, but I do believe that it is an important state responsibility.

Look, out of the top 300 metropolitan areas with the highest poverty, 77 of them are in California. It’s connected to the achievement gap. We haven’t done enough to address this issue.

Q: What are your concerns as the state board develops its new evaluation system?

A: One concern, it’s taken them three years. The second concern is related to a lack of urgency. Look, it was hard but we went from a 44 percent graduation rate to 72 in LA Unified. It is possible.

Everyone said to me: “That’s not the mayor’s job. It’s too hard. Why’d you take it on?” I said, “If not me, who?”

For me, I’m here today because there was a public school that gave me a second chance. I was kicked out of Catholic high school. Public school gave me a shot and I daresay if people would have said back then, “He’s poor, his mother never graduated from college, his father had a second-grade education, he grew up in a home of domestic violence with alcoholism, he’s going to be a janitor.” Guess what? There were people who said that.

Q: What drove up the graduation rates in Los Angeles?

A: We set high standards. We focused on teacher training, we focused on staff development. We got the parent college (which sought to improve parent involvement). We integrated blended learning and technology in our classrooms. And we set high standards for our kids. Everywhere I go I say, “Do you believe in you?” And our kids have to say, “I believe in me.” It’s what my grandmother did with me.

So I don’t think we can accept the notion that we’re destined to be in jobs that our parents have; that if our parents didn’t go to college, we’re destined to not go as well. That’s just absolutely unacceptable. I don’t buy it.

We teach parents rights, roles and responsibilities. But not just rights. We teach them they have roles and responsibilities as parents.

Full Credit to Reporter Judy Lin at CALmatters. calmatters.org