My good friend and I were talking about how to help kids do better in school when she told me something surprising. She had a hard time in school herself, and she said that she thought it was partly because her parents never talked to her about school. They never asked how her day went, or what she did that day, what homework she had, or if she needed any help. She said that she was struggling with math, but she didn’t tell them and she was too embarrassed and scared to ever dare to approach anyone else about it.

“I wish my parents had made me feel comfortable, so that I could have asked them for help,” she said. It would have been so easy: “How are you doing in school?” or “Do you need help with anything?” or even “How was your day?” might have opened the door so she could have said: “Help! I’m doing horrible in math and I don’t know what to do.” But it didn’t play out that way for her.

My friend’s parents are good people with good intentions about parenting. The problem for my friend was that they didn’t understand that simply communicating with children allows them to communicate back. And it turns out that’s something a lot of parents just don’t know.

She and another friend who had a very similar experience are both Latino, and it may be their cultural background that influenced how their parents talked to them. But apparently it isn’t only Latinos who fail to nurture communications about school. A nurse I once knew, who was Japanese, told me she admired my relationship with my daughter and often asked me for advice on how to talk to her own two daughters. It was so surprising to me that an educated professional like her would be asking me for parenting advice.

Well, as it turns out, this situation is not at all uncommon, especially among immigrant parents. In a research paper for the Wilder Foundation, a Saint Paul organization dedicated to serving the vulnerable and disadvantaged, author Thao Mao says that although immigrant parents usually place a high value on education, “foreign-born parents are less likely to visit their children’s school, participate or attend school activities and events, help with homework, and talk to teachers and school staff.”

Among the reasons for this imbalance, the paper cites “lack of formal education, low English language proficiency, lack of knowledge of the mainstream U.S. culture and school systems, and time constraints due to work and family responsibilities.”

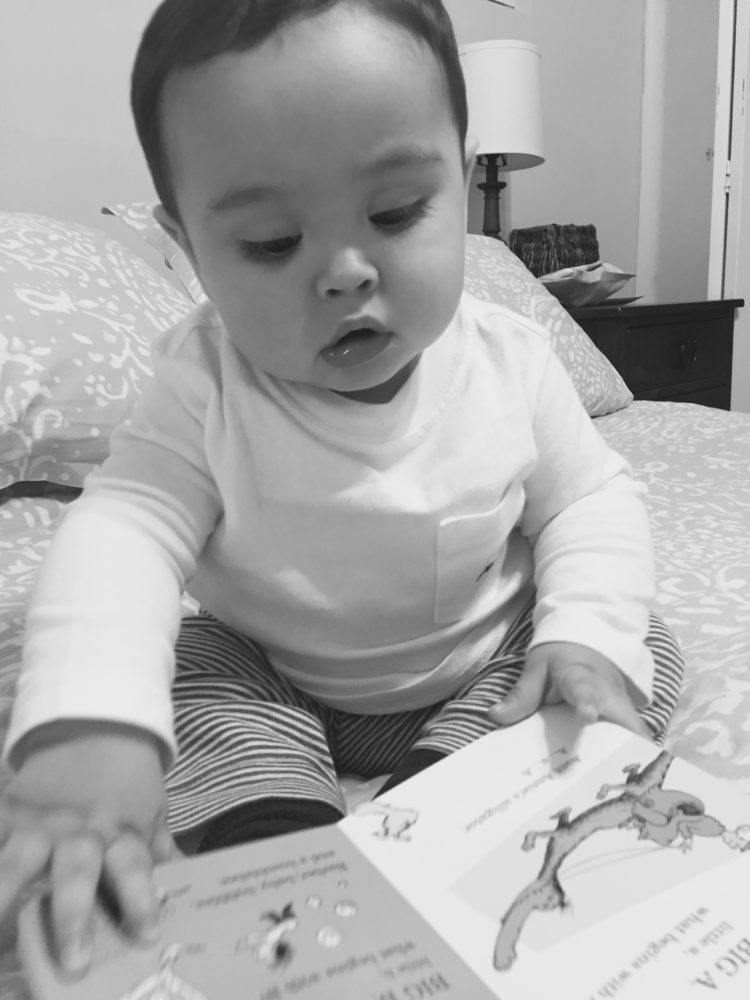

But there are signs of change. Various programs are being developed to try to help schools work harder to engage the Latino parent. Members of a doctors’ organization called Reach Out and Read, which promotes reading to children as a way to increase literacy, distribute books to all of their pediatric patients and offer reading advice to the parents at every doctor visit. And one book, I Love You Like Sunshine by Dr. Mariana Glusman, helps parents understand the importance of reading to children even starting as early as infancy. Her book, designed to be looked and read to babies, also explains the role of talking with babies in early brain development.

It’s difficult to comprehend how otherwise kind, loving, supportive parents don’t realize the effect they have on their children’s development. Because of poor communication, my friend felt disconnected from her parents, and this caused feelings of isolation and loneliness for her that affected her work in school. And immigrant parents have to overcome more barriers than most in learning to communicate with their children. But for parents with children, the good news is that doing it is easy and it’s not too late to turn things around.