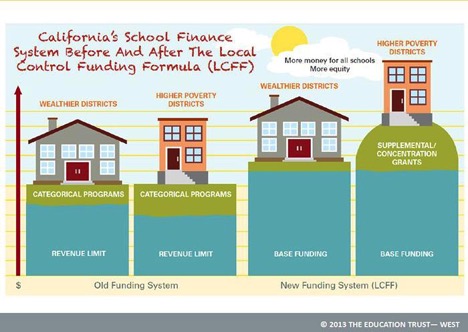

School funding has been a polarizing topic for years. Under the old California school funding system, local education agencies, which include districts, charters and other education organizations, were funded through “a unique revenue limit, multiplied by its average daily attendance (ADA)” in addition to funding that was restricted to numerous categorical programs. These programs were designed to provide targeted services based on the needs of each district but were restricted to only being used under specific “categories.” In an attempt to steer away from these restrictions and to provide more flexibility to districts to decide how to allocate funds, the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) was introduced.

According to a recent report in the Los Angeles Times, “The Local Control Funding Formula intended to remedy educational inequities by giving districts extra money based on how many of their students were in high-needs categories: low-income children, foster youth and English learners.” Thus, with the introduction of LCFF, both revenue limits and categorical programs were eliminated. In the beginning, parents and education advocates demonstrated strong support as they hoped this would allow for districts in lower income communities to have more funds come in to support additional programs and support services for those who most needed it. The reality, however, has shown that the added flexibility has not necessarily garnered the outcomes expected.

In efforts to evaluate how successful LCFF has been in delivering its promise of giving students who need it most, access to more resources, the Education Trust-West, an Oakland based non-profit that advocates for educational equity, released a report, The Steep Road to Resource Equity in California Education: The Local Control Funding Formula After Three Years, finding that as intended, LCFF has improved funding equity among districts. Unfortunately, it also found that even though districts with the largest concentration of low-income students were receiving more state and local funds than their more affluent counterparts, students in the highest poverty schools were still provided far less access to services and opportunities than students in the lowest poverty schools. While the report surfaced during a time where allegations that several school districts had misused their extra funding, the study also sheds light on other restrictions that have not been lifted, further constraining LCFF’s initial purpose.

The reality is that local education agencies are still forced to operate under many of the same policy constraints as before in addition to new laws. For example, in my own district (currently serve on the Board of Education for Lynwood Unified School District), our funding increased dramatically given our student demographics. Even so, we are limited in our ability to fund additional resources for our students as we are having to use our district’s extra money to cover the increases in healthcare and pension costs amongst many other costs. While this is just one example, the added responsibility for districts to cover a higher percentage of pension costs is one that can cost millions of dollars per year; this is money that is being taken out of the overall budget. For districts like ours, this added financial cost is a burden as it eliminates the “extra funds” and actually sets us even further back from the funds we used to receive under the old funding system.

But resources alones are not enough to close the “opportunity gaps.” While I know first hand that our district has been proactive and taken advantage of LCFF to go as far as funding an entire Equity Department as a new layer of accountability and support, our creative attempts to be an equity-based school district can only take us so far with the added constraints to our so-called “locally controlled” budget.

Alma Renteria

Latest posts by Alma Renteria (see all)

- Rincón Universitario: Cómo Escribir una Narrativa Auténtica para Solicitudes de Universidades, Parte 3 - October 17, 2019

- College Corner: How To Write An Authentic Narrative for College Applications, Part 3 - October 15, 2019

- Rincón Universitario: Cómo Escribir Una Narrativa Auténtica para Solicitudes Universitarias, Parte 2 - October 1, 2019

- College Corner: How To Write An Authentic Narrative for College Applications, Part 2 - September 26, 2019

- College Corner: Cómo Escribir un Relato Auténtico de Solicitudes para la Universidad, Parte 1 - September 4, 2019