Dr. José Manuel Villareal was raised in Blythe, California in a family of farmworkers. Blythe, an agricultural area in Riverside County, sits by the Colorado River near the California and Arizona border. His father José Macario Villarreal, was an active part of the Farm Workers Movement with Cesar E. Chavez, who taught his son to pay attention to his community, identify where help was needed, and do all that was possible to fill that need. Moreover, José Manuel was raised by a village of strong Mexican women, including his mother Maria Irene Villarreal, who shaped who he is today. Hard work, courage, and commitment to social justice were woven into the fabric of José Manuel’s childhood and set the foundation for his career as an educational leader.

José Manuel has a kind face, rounded, unlined, and shares an easy smile. He has a twinkle in his eyes that sparkles brightly when talking about his childhood, his family, his work with our youth, teachers, and our community. He began his career in education as a college tutor and mentor, became a school counselor in Riverside County, and after being given the opportunity to be an assistant principal and principal in Vista (in San Diego’s North County), he became a Senior Director for the Juvenile Court and Community Schools with the San Diego County Office of Education. He earned his doctorate in Educational Leadership through the University of California, San Diego and California State University, San Marcos. He now serves as the Vice President of Epiphany Prep Charter School, a Charter Management Organization that operates in San Diego County.

When I think of a luchador/a, a warrior, I think of the women and men who raised me. I think of those people who were the “firsts” in their family. The first to graduate from high school. The first to graduate from a University. I also think of those who use their position as a “first” to serve others, and lift others in our community. I chose Dr. José Manuel as the first person to be recognized as a San Diego Luchador because of his determination and success in serving students of color in the neediest regions in San Diego. I sat down with Dr. José Manuel to discuss his work, and to discover what could be learned from him.

What was it like growing up in Blythe, California?

I felt and saw the injustice that pushed my dad into the bracero movement. My dad was a farm worker activist that ignited my commitment to justice. There are people that don’t have a voice, that are misrepresented and set up for failure in our country battling poverty and classism. Someone needs to be their voice and advocate.

I was an English Language Learner and when I started school, I was pulled from the classroom to learn English for an hour, and my friends asked where I went. I knew that I was different. Once I learned English, I became the voice for my family, translating for my mom at doctor’s appointments and social services. As a child, I worked in the fields and had my first job at 10 years old at a gas station in Blythe. My family and circumstances always taught me to work hard and that I have a responsibility to my community and must provide a voice for the voiceless.

How did your experience in school impact your decision to go into Education?

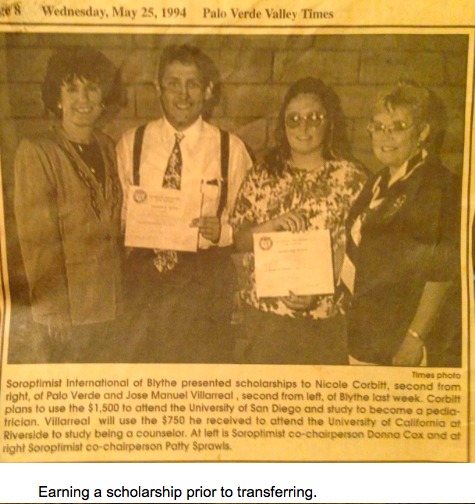

In high school, I was one of two Latinos in a ninth grade honors class. I thought to myself, if I can be in this class, then I can go to college. I always thought I wanted to be a car mechanic because that what I saw in my neighborhood. My school counselor, Mr. Scott, was my first exposure to the world of counseling. When I made the decision to go to college, then I thought the closest major to mechanics would be engineering. As a senior in high school, I applied to UCSB and CSUSB, was accepted but couldn’t afford it. I knew my only path was to attend the local community college and transfer to a four-year university subsequently.

While a community college student in Blythe, I began to work with, the now deceased, Rodolfo Piñon who worked as a counselor for a substance abuse center in Blythe. He worked with people with DUIs and addicts who were reintegrating into the community. I became a volunteer with him at a domestic violence shelter.

After transferring from community college to University of California, Riverside, I was hired to work with the Early Academic Outreach program to be a mentor for high school students. I tutored and supported kids with college applications. At twenty-one years old, I was part of group of undergraduate psychology class project that worked with battered incarcerated women at Chino prison.

I expected to go into huge warehouse like building to see evil and saw instead women who were soft, warm and loving. My first day I showed up in jeans, which was not allowed, and I had to put on a yellow jumpsuit. My very first session with the woman, and as they saw me enter the room in that ridiculous outfit they burst out laughing. One woman said, “Come here baby,” as they laughed, falling out of their chairs. This is when I knew I wanted to be a counselor.

What made you decide to leave the traditional school system, which you had been a part of your entire career, to join the Charter movement?

On a visit to East Mesa Juvenile Detention Facility, I saw a student that I expelled in middle school. I realized that I played a part of the pipeline from school to prison. I felt sick and thought to myself, “We messed up. We are a part of the system that keeps our youth and community in poverty.” It was then that I knew I had to go back to the non Juvenile Court system and back to an urban school where I could work with students before they become involved with the justice system. It was then that I decided I needed to go back to a K-12 setting to make an impact and joined Epiphany Charter School and was hired to open the school in Escondido.

What have been your successes and challenges in the charter school system?

In San Diego County, there is a saturation of charter schools in the metro region, but this is not the case in North County. There is a large community of low income students whose needs are so great; more choice is to be created to met their needs. As the principal opening a new school, it was my job to recruit and enroll students. I was out in the heat of July in 2015, wearing a shirt and tie, trying to talk to families and handing out fliers at local mercados. Although I engaged with potential parents and students in both Spanish and English, I was having a hard time convincing them that I was not Immigration and Customs Enforcement. I realized that I had to change my strategy. I started telling parents my personal story, stopped wearing that damn tie, rolled up my sleeves, and connected with our community through authentic conversations. We had a successful school opening and celebrated almost 500 students enrolled at the start of our second year. Our success has been in working with parents, supporting them in becoming empowered by understanding the school system.

What advice do you have for other educational leaders?

Leadership is not about you. Please ask yourself, “How can I impact the lives of those who are the most vulnerable?” Leadership is about always trying to help, always giving back to the community. I was raised by my father and mother to be this way and I’m trying to teach the same to my sons (ages eleven and eight). For example, we do beach cleanups and donation drives. And, when we see someone in need out in the community, we try to understand their story and find a way to help.

Pingback: OHS Welcomes New Principal : OHS Foundation

Beatrice Rincon

Proud to say I’m a retired person that worked for Riverside County Mental health in the small town of Blythe Ca.And have always seen the need to help others. Also Proud to have known the Villarreal Family.