Over the last several weeks, I have been teaching a unit titled “Racial Profiling.” A broad overview for this unit reads like this: students read Bob Herbert’s essay titled “Jim Crow Policing,” published by the New York Times in 2010, then they analyze the use of passive sentences in Herbert’s essay, then students choose a random controversial issue and write an essay in which they avoid using passive sentences. I was bothered by the superficial set-up of this unit, so I changed it and created a new unit that taught the use of passive sentences, but also focused exclusively on race and racism in America.

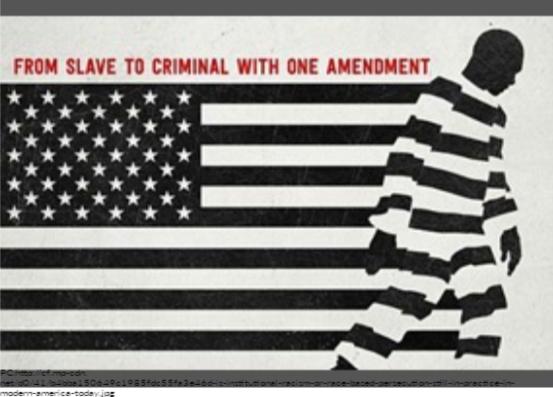

I began by defining race as a social construct created by white, European men for the exclusive purpose of defining social power dynamics. Since its inception, the “social contract” was designed to create two subgroups within the human race: whites and nonwhites; the former would hold all social power, and the latter would agree, either through physical force or psychological manipulation, to a socially subordinate role. I taught my students about Foucault’s theory of Biopower, the idea that a dominant entity can subjugate and control the body of subordinates through systemic routines and practices, and its impact within the American police system. We explored Utilitarianism, the idea that actions (even immoral actions) are justified as long as the outcome benefits the majority, as a driving force behind economic capital gains in America made off the backs of nonwhites. I also called out the education system, and my school specifically, for perpetuating principles of colonization, such as making English the “standard” language, and forcing our students to wear uniforms — one of the most basic methods of “othering” and controlling a colonized peoples.

This last portion caused many of my colleagues, most of which are people of color, to question the content of my lectures. They were uncomfortable when I criticized the fact that my school hires white teachers to come into urban schools and teach students of color who have little to nothing in common with their culture. My colleagues of color were also uncomfortable with my lecture style because it resembled a sermon where I devoted 45 minutes to talking through issues of race; according to my colleagues, there was too much “teacher-talk” and not enough “student-talk.” They suggested that the sermonic nature of my lectures could lead to indoctrination rather than critical thinking.

I was surprised by the reactions my colleagues of color had to my lectures on institutionalized racism in America. I thought that they would applaud the attempt to expose our kids to the realities of institutionalized racism, but they instead met me with resistance, telling me that people of color need white allies, and “if you want to climb up the administrative ladder and make real change within our education system, you must soften your rhetoric so that white people are willing to listen.” In beautifully metaphoric language, they told me that I was burning through networking bridges that I hadn’t yet built.

Is this reaction due to internalized oppression? Is it due to the fact that I was, for all intents and purposes, indoctrinating my kids after all? I am still grappling with the resistance educators of color expressed against such a raw view of racism in America, but I am mostly worried about the self-perceived role of an educator of color within the American education system. Are educators of color in the education system to resist, or are they there to maintain a status quo that perpetuates white supremacy? From the experiences I’ve had as of recent, I fear that educators of color are too afraid to speak against systems of oppression, and I am more frightened by their fear to rock the boat than by the consequences I might face for rocking the boat.