I vividly remember the Scholastic book magazines that my elementary school teachers handed to me as Scholastic book orders came near. I would ruffle through the pages and look for the most enticing book covers. When the school bell rung, I would towards the school exit and into my mom’s car, and I’d start asking her to buy me books from the magazine. Once in a blue moon, my mom would agree to buy me one or two books, and I would wait with excitement for the books to arrive. Once they arrived, I would read the first page, close the book, and never open the book again.

I now think back on that process, and I am astounded by the power that modeling behavior has on children. The reason I was never able to finish a book is simple — I spent most of my time watching television. I cannot claim that I was more interested by television than I was interested in reading books. I enjoyed both. The reason I spent more time watching television than I spent reading books is because my family did the same. Our weekend family nights consisted of watching a movie or two. On weekdays, my parents would get their daily dosage of media and news updates from the 5 o’clock news, and that would bleed into the 6-10 o’clock television binge watching. As a family, we spent an average of 45 hours per week watching television; that’s a full-time job, plus overtime.

I seldom saw my mom read a book, and the only book I ever saw my dad read was the bible—he was a preacher, so he couldn’t escape his literary reality. As the son of Latino immigrants, I shared in the same reality that many younger Latino generations currently experience. According to a 2018 PEW research study, “Hispanic adults are about twice as likely as whites (38% vs. 20%) to report not having read a book in the past 12 months. But there are differences between Hispanics born inside and outside the U.S.: Roughly half (51%) of foreign-born Hispanics report not having read a book, compared with 22% of Hispanics born in the U.S.” Nearly half of Latino immigrant parents do not read books, but the average number of televisions in Latino homes is steadily increasing year-after-year.

Latinos make up the majority of the student population in California, and they also make up a significant amount of students whose literacy proficiency is far below grade-level. Yes, the poor education that Latino students are receiving in school is a major player in their low proficiency, but parents are also contributing to the low proficiency levels. When parents model indifference towards education, their children will reflect that attitude. I will take this moment to state that throwing a tantrum when we see a failing grade on our students’ report card is not honest educational engagement. Your child knows this, and your child’s teacher knows this. I have come across too many parents who try to show investment in their child’s education by getting angry over failing grades at the end of the semester, but are eerily absent the rest of the time. That’s momentary engagement, and your child, not surprisingly, behaves in the same manner at the end of each semester. If parents model momentary educational investment, how should their child behave any differently?

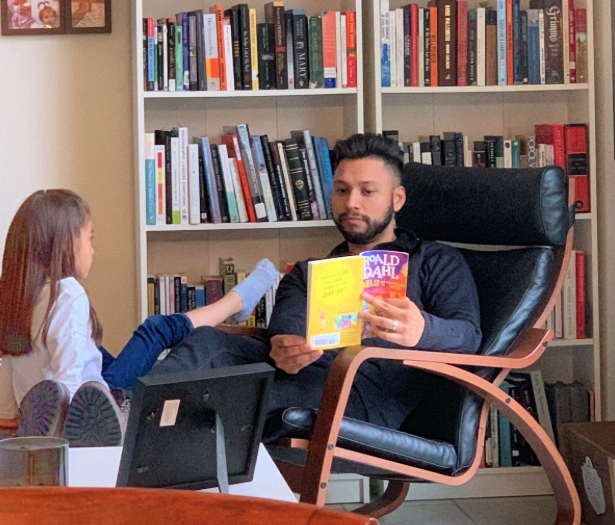

Parents must actively participate in academic and educational practices at home to reflect an honest and thorough engagement with education. Parents have the power to elevate their children’s literacy proficiency by modeling effective literacy habits. Simply put, if you want your child to pick up a book at home, you must do the same. If you want your child to improve their vocabulary, you must also improve your vocabulary. If you want your child to get off their phone, and improve their literacy levels, you must get off your phone and improve your own literacy levels. Children are their parents’ reflection. If you model passivity towards education, your child will be passive. If you model television binge-watching, your child will also binge. If you model reading to your child, your child will read.